***The following content is for general informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. While it provides insights into legal issues, it does not create an attorney-client relationship. For legal advice, please consult a licensed attorney.***

(TL;DR at the bottom)

Opening Statement

Our last article, Performance Royalties and PROs: What They Are, When They're Generated, Who Gets Them, and How They're Collected, focused only on performance royalties. As a reminder, performance royalties are payments earned by songwriters and publishers whenever their music is publicly performed or broadcast, including on radio, streaming platforms, live venues, and TV.

Now let’s jump into the other categories of royalties.

This article aims to (a) explain the other types of royalties so that you can have more informed discussions with your band, industry professionals, and representatives, (b) familiarize you with key terminology so you can identify potential contract issues and know when to seek professional advice, and (c) help you be a strong advocate for yourself and your band.

First, we’ll briefly recap some key concepts. Second, we’ll define royalties in general. Third, we’ll list out the various categories of royalties, how they are generated, who earns them, and how they are collected. Fourth, we’ll share a table that compares all the types of royalties. Last, we’ll give some tips for making sure you’re not missing out on all these royalties.

As always, underlined terms are links that will shoot you to specific sections of prior relevant articles.

Rewind

Here is a snapshot of some key concepts that you need to keep in mind as you read this article:

1. One Song, Two Rights

A recorded song consists of two distinct legal rights, each of which can have different owners and generate separate streams of revenue:

The “composition copyright” - the song itself (the melody, lyrics, chords, structure, etc.) (aka: “song copyright”). Certain royalties are paid to those with rights in the composition.

The “master copyright” - the actual recording of the song (aka: “sound recording copyright”). Other types of royalties are paid to those with rights in the sound recording.

Here is our article explaining this concept.

2. “Rights Holder”

If you own any rights in a song, you are considered a “rights holder”. This includes rights in the composition, and/or rights in the sound recording.

3. Music Publishers

A music publisher is a person or company that promotes songs and ensures that songwriters (and/or other owners of the composition) receive royalties and licensing fees when their songs are played or used. There are pros and cons to using a publisher, and you do have the option to self-publish. The publisher, whether it’s you or a third party, holds rights and receives some royalties.

Here is our article on music publishing.

Royalties Defined

In plain English, royalties are payments made to rights holders whenever a song is used (i.e., played, reproduced, distributed, performed, streamed, licensed, etc.). The type of royalty and the way it’s collected and paid depends on how the song is used (is it played on the radio? Or is it downloaded or physically reproduced? Is it being covered? Or is it streamed? Or is it licensed for use in a commercial? And so on and so forth).

Types of Royalties

Below is a simple list of the various categories of royalties. Each will be further expanded in the sections that follow:

Performance royalties

Mechanical royalties

Synchronization (“Sync”) royalties

Print royalties

Neighboring rights royalties

YouTube Content ID royalties

Master recording royalties

Backend royalties

You’re probably wondering, “but what about streaming royalties?” or, “what about covers?” Great questions. These things/scenarios are not categorized separately because they can fit into different established categories based on the terms of each deal made. But you will hear these terms used often, so take note of the different categories they can possibly fit into.

It’s also good to note that the amounts of both performance royalties and mechanical royalties are governed by law, while the others are determined by industry standards and private negotiations between the contracting parties.

1. Performance Royalties

We did a broad stroke overview of performance royalties and PROs (Performance Rights Organizations) in our last article. That article serves as an introduction to performance royalties and how PROs function and calculate the royalties that you receive. In short, performance royalties are earned by composition rights holders (with a small exception for some streaming - keep reading) whenever their music is publicly performed or broadcast on radio, streaming platforms, live venues, and TV. Performance royalties are collected and paid out by PROs.

Now, to go a bit deeper, there are several sub-categories of performance royalties:

(i) Terrestrial (Traditional) Performance Royalties - Generated when a song is played on traditional (terrestrial) FM/AM radio, TV, at live venues, and in public spaces. These royalties are collected by PROs and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

(ii) Digital Performance Royalties (non-interactive) - Generated when a song is played on non-interactive digital platforms. “Non-interactive” means, essentially, that the listener does not get to choose what song is played next (think of a Pandora radio station or Sirius XM). These royalties are collected by SoundExchange and paid to those that hold the rights in the sound recording (as opposed to those that hold the rights in the composition).

(iii) Interactive Streaming Platform Royalties - Generated when a song is streamed on interactive digital platforms. “Interactive” means that the listener can choose what songs to listen to (Spotify, Apple Music, and the like). Now, pay close attention. Interactive streaming generates 2 different types of royalties: (1) performance royalties and (2) mechanical royalties (more on those in the next section). Interactive streaming platform royalties are collected by their respective organizations (PROs collect the performance royalties, and mechanical rights organizations collect the mechanical royalties), and are paid to their respective rights holders (the performance royalties go the those that hold rights in the composition, and the mechanical royalties go to those that hold rights in the sound recording).

(iv) Theatrical Performance Royalties - Generated when a song is performed or played in live theater productions, like a Broadway or local play. These royalties are collected by PROs and theatrical rights organizations, and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

(v) Background and Ambient Music Royalties - Generated when a song is played in businesses and public spaces, like the gym, mall, elevator, airport, etc. These royalties are collected by PROs and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

(vi) Live Performance Royalties - Generated when a song is played live, whether at a massive festival, in a small venue, or anywhere in between. These royalties are collected by PROs and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

(vii) TV and Film Production Royalties (aka: “Cue Sheet Royalties) - Generated when a song is played, either as background music or a specific scene, in a commercial, movie, or TV show. These royalties are collected by PROs and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

(viii) Sports and Event Performance Royalties - Generated when a song is played at a sporting event or other major public event. These royalties are collected by PROs and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording).

2. Mechanical Royalties

Mechanical royalties are generated when the composition of a song is reproduced either on physical media (CDs, tapes, vinyl, etc.) or when downloaded digitally. They’re called “mechanical” royalties because the process of reproducing songs in the past involved the mechanical processes of physically making cassette tapes, pressing vinyl, burning CDs, etc. However, the meaning of the term has expanded to now include digital reproduction.

Mechanical royalties are collected by mechanical rights organizations (MROs) and paid to those that hold rights in the composition (not the sound recording). These are some of the major MROs in the US:

The Mechanical Licensing Collective (The MLC) – Handles digital mechanical royalties from interactive streaming platforms in the U.S. (Spotify, Apple Music, etc.).

Harry Fox Agency (HFA) – Traditionally collected mechanical royalties for physical and digital downloads but now primarily focuses on licensing services.

Music Reports, Inc. (MRI) – Offers licensing and royalty administration services, mainly working with digital platforms.

Mechanicals: Downloaded vs. Streamed

An important distinction:

When a song is downloaded (as opposed to just streamed), each download generates mechanical royalties.

When a song is streamed interactively (meaning the listener gets to choose what’s played, unlike they would on a radio station), a portion of the revenue from each stream is allocated to mechanical royalties, and another portion is allocated to performance royalties.

Non-interactive streaming (where the listener does not get to choose what song is played next) generates only performance royalties.

We won’t get into tethered downloads in this article, but just know that’s a thing (i.e., when Spotify lets you download a track, but if you end your Spotify subscription, you lose the track - that’s a tethered download).

3. Synchronization (“Sync”) Royalties

Sync royalties are generated when music is synced with visual media including video games, movies, TV shows, commercials, etc. In these scenarios, the person or entity that wants to use a song in their visual creation must purchase a license to use the song. Sync royalties are paid to both the rights holders of the composition and the rights holders of the sound recording.

Think of sync royalties as a “one-time” earning event resulting from the sale/purchase of a license; Sync royalties are generated from the sale of the music license, not every time the thing is replayed. So what happens when the episode or commercial that your song is in is replayed? Each replay then generates performance royalties, which, we know by now, are collected by PROs and paid to the rights holders in the composition (not the sound recording).

The license fee that’s paid up front is called an “upfront sync fee,” and the performance royalties received from the song’s replayed use are called “backend royalties”. The upfront sync fee is paid directly from the licensee (person or entity buying the license to use the song) to the licensor (persons or entities selling the license) before the song is used. The backend performance royalties are then collected and distributed by PROs as per usual (more on backend royalties later in this article).

Sync deals can be negotiated independently, or by sync licensing companies. Sync licensing companies use their contacts, knowledge, experience, and infrastructure to help artists license their songs, and, of course, they receive a cut of the licensing fee.

There are several sub-categories of sync royalties: (i) Film and TV Sync Royalties, (ii) Commercial and Advertising Sync Royalties, (iii) Video Game Sync Royalties, and (iv) Online and Social Media Sync Royalties.

4. Print Royalties

We love history here! Print royalties are one of the oldest forms of royalties. The first hints of music notation that we know of come from monks in medieval Europe in the 9th century. Before that, every song was passed down through oral traditions and had to be completely memorized. Sheet music was arguably the first “music industry.” Millions of copies of sheet music were being sold in the 1800s! Today, print royalties are still important revenue streams for composers, songwriters, and publishers.

Print royalties are generated when the lyrics or sheet music of a song are published, sold, or reprinted in physical and digital form. There are a few sub-categories: (i) Physical sheet music sales (for example, an orchestra purchases 50 physical copies of an arrangement), (ii) digital sheet music and downloads (for example, that orchestra instead purchases 50 digital downloads of the arrangement), and (iii) lyric reprint royalties (for example, your lyrics are printed in a book or posted on AZLyrics.com).

Print royalties are collected by the publisher. If an artist is independent and does not have a publisher, they’ll need to register with a print music distributor in order to receive royalties. I’m hoping that with all we’ve gone through, you can guess who received print royalties - the owner(s) of the composition (not the owner(s) of the sound recording).

5. Neighboring Rights Royalties

This is a good spot to refresh your memory on the one-song-two-rights concept. Neighboring rights royalties are generated when a sound recording is played in public (TV, in public places, and on certain digital platforms (non-interactive), and terrestrial and/or satellite radio). Neighboring rights royalties are paid to anyone with rights in the sound recording of the song, including the performers (those who performed on the sound recording). Neighboring rights royalties are collected and paid out by neighboring rights societies.

They are called “neighboring rights” royalties because they are for the use of the sound recording, which is next to (“neighboring”) the composition.

Here’s an [overly-simplified] example to illustrate the difference and eliminate confusion with regard to performance royalties: A recorded song is two things - the composition, and, separately, the sound recording. Suppose that you own the composition rights in a song and that your label owns the sound recording rights in the same song.

When you perform the song at a live show, you receive performance royalties (because the composition, the thing you own, was used) and the label receives nothing (because the sound recording, the thing they own, was not used). In this example, no neighboring rights royalties are paid.

When the recorded song is played over the speakers at a bar, you receive performance royalties (the composition, the thing you own, was used) and the label receives neighboring rights royalties (the sound recording, the thing they own, was also used).

A not-so-fun-fact about neighboring rights royalties is that the US is one of the only countries that does NOT pay neighboring rights royalties for songs played on terrestrial AM/FM radio (?!?!).

6. YouTube Content ID Royalties

YouTube’s Content ID System is an automated copyright management system that helps rights holders track, monetize, or block unauthorized use of their copyrighted content. YouTube Content ID royalties are generated when a song is used in a YouTube video and monetized via Content ID. These royalties are collected by YouTube and paid to rights holders of sound recordings and of the compositions. Independent artists need to register through a distributor (CD Baby, TuneCore, DistroKid) or publishing admin service (Songtrust) to collect their share.

If you want to upload an original work to YouTube and receive YouTube Content ID royalties, you first want to make sure it meets their content ID criteria. They’re a bit elitist, though, and usually let only record labels, music publishers, movie studios, distribution services, or big content creators “pass go.” However, if you’re a small or independent artist, you can still squeeze in with the help of a third-party service, such as a music distributor that already has access to YouTube’s Content ID System (CD Baby, TuneCore, and DistroKid are a few).

Once a song is added to YouTube’s Content ID database, it’s given a “fingerprint” based on its melody, rhythm, waveform patterns, frequencies, etc. Every new video uploaded to YouTube is then compared to the database of fingerprints, and, if a match is found, the new video will be flagged and the owner of the original content will be alerted. The owner of the original will then have a few options: monetize it (ads are placed and revenue goes to owner of the original), leave it up and track it for useful analytics, remove the content entirely, restrict the content to certain geographical locations, or issue a “copyright strike” (after so many, the channel could be suspended or shut down).

7. Master Recording Royalties

Generated when the sound recording (aka: the master) is licensed, streamed, distributed, downloaded, or sold. Master recording royalties from streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music) are paid to labels or independent artists via their distributor. Sync royalties from master recordings are paid directly by sync agencies or licensees to the sound recording rights holder.

8. Backend Royalties

“Backend royalties” is more of a classification rather than a separate category of royalty. It’s a general term that applies to many of the categories listed above, and refers to when a song generates ongoing royalties from any initial deal. For example, you license your song to be used in a commercial. You collect a sync licensing fee up front. Every time the commercial is replayed, it generates performance royalties for you. In this situation, those performance royalties are also classified as backend royalties, since they generate ongoing income after the initial licensing deal.

A common flavor of backend royalty is the kind that producers can negotiate to receive; they’re typically called “producer points”. In general, each point is equivalent to 1% of the net revenue from a record's sales or streaming royalties, and the producer points usually come from the artist’s share. For example, a producer that’s heavily involved with the creation of an album can negotiate for, say, 4 producer points, which is equivalent to 4% of the total revenue. Once revenue is calculated, the artist pays the producer their 4% from the artist’s portion.

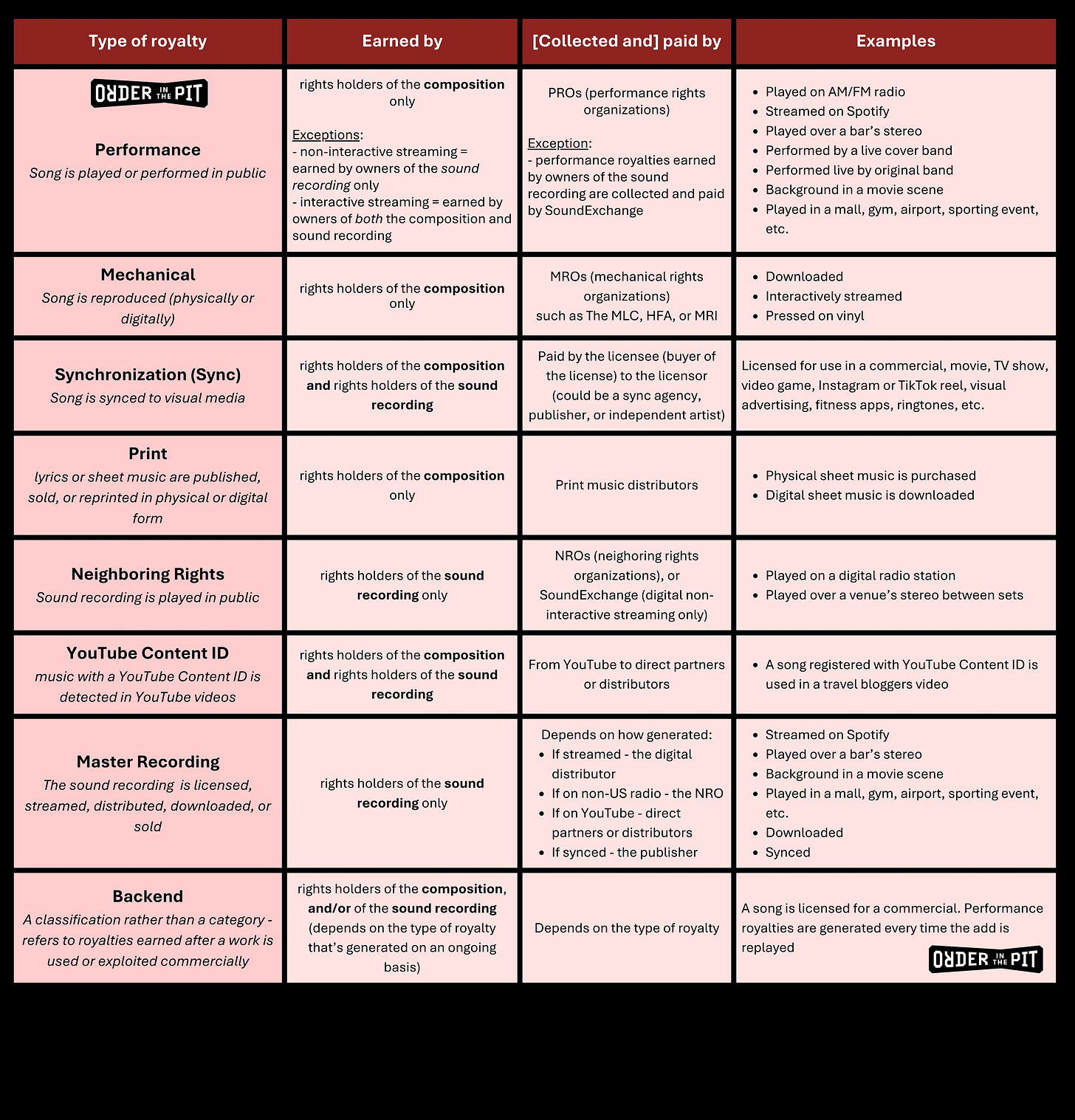

Table: Comparing Royalties

The table below is my attempt to summarize and compare the various categories of royalties. This table is for illustrative purposes only, and is subject to revisions.

Don’t Miss Out on Royalties

By now you’ve probably realized that receiving royalties is in no way automatic or guaranteed, and that it requires a lot of organizational and administrative duties. Although being a musician is a creative endeavor, it’s also a business. If you can afford it, it’s good to hire an administrative service to help you keep track (you’ll still have to keep your eyes on them!). But, that’s easier said than done, especially if you’re a new or small act that isn’t YET raking in heaps of cash. Here are a few steps you can take to make sure you’re collecting as many royalties as possible:

REGISTER YOUR COPYRIGHTS (see our article on intellectual property and how to register a copyright with the US Copyright Office here).

REGISTER SONGS PROPERLY and with the correct royalty collection organizations:

For performance royalties - register with a PRO (ASCAP, BMI, etc.)

For mechanical royalties - register with MROs (The MLC, Harry Fox Agency, or an independent admin service like CD Baby)

For neighboring rights royalties - register with neighboring rights societies (for digital performance royalties in the U.S., register with SoundExchange. For full neighboring rights royalties (including international and terrestrial radio), register with PPL (UK), GVL (Germany), Re:Sound (Canada), or other neighboring rights societies)

For YouTube Content ID royalties - register directly with YouTube Content ID, or a music distributor with access (CD Baby, TuneCore, Songtrust, etc.).

Thoroughly negotiate and get all deals and agreements IN WRITING.

Use a SPLIT SHEET with your band and everyone you write or record with. A split sheet is a simple document that states who wrote, contributed, recorded, or whatever to a song. It eliminates disputes later, and can even be a fun exercise.

Use an established digital distributor if you want your songs to be properly tracked on digital streaming services.

TRACK YOUR OWN STUFF. No one, no company, will look out for you as good as you will. Some royalty tracker tools for you to consider include SongTrust, Royalty Exchange, SplitSheets, and Master Tour. None are perfect, so ask around, and do your research.

STAY ORGANIZED. For this, and just in general. Have a good physical and digital filing system. Take notes. Set yourself up for success.

TALK TO OTHER ARTISTS. Don’t be afraid to ask the bands you play with or look up to how they manage royalty collection. This will also help you forge connections, which is good for you and your band.

RESEARCH. Read. Listen. Learn. Ask. There’s always more to know and room to improve your existing methods and protocols.

Hire professionals and consult with experienced advisors. A few hours of an attorney's time can avoid very expensive problems down the line.

Closing Remarks

Once again, what was meant to be a brief summary has turned into a lengthy piece (that still only brushes the surface). My hope is that you now have a better understanding of royalties, can have more informed discussions with your band and industry professionals, and that you’re in a better position to advocate for yourself and your band as you navigate your growth and explore opportunities with a healthy dose of caution.

As always, the topics covered here contain more twists, turns, and caveats than can possibly be addressed in a single article, and attorneys are constantly wrestling with the gray areas of the relevant laws. This article is merely a broad stroke of the fundamentals and should not be considered as a complete explanation of royalties in any way.

Let us know what other topics you’d like to know more about.

***The above content is for general informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. While it provides insights into legal issues, it does not create an attorney-client relationship. For legal advice, please consult a licensed attorney.***

TL;DR

Musicians can make money from multiple types royalties, including performance, mechanical, sync, print, neighboring rights, YouTube Content ID, master recordings, and backend royalties, but collecting them isn’t automatic nor guaranteed. To get paid, you must get all deals in writing, register with all of the appropriate royalty collection organizations, and stay on top of tracking. Music is a creative endeavor, but it’s also a business; treat it like one. Stay curious, educate yourself, talk to other professionals, and be the advocate for yourself and your band.